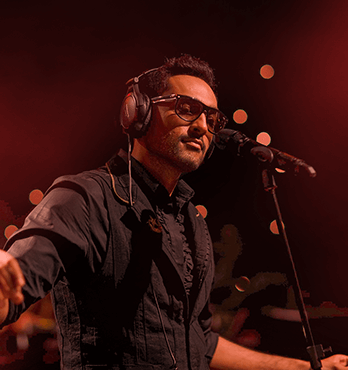

Ali Sethi

by Ayesha binte Rashid

As he waits to go into his first rehearsal with Coke Studio’s house band, Ali Sethi brings up a piano app on his phone. Holding it up close to his ear, he presses the screen and vocalizes the notes he’s playing on the piano. Any free moment, it seems, is an opportunity for riyaaz (vocal practice). Within half an hour of entering the studio, Ali has wrapped up the rehearsal for Gulon Mein Rang.

Ali’s romance with classical music began early in life — a 5-year-old Ali would be called out by his mother to perform in front of guests and would happily oblige, singing classical tunes like Mujhse Pehli Si Mohabbat to a room full of praise. His mother’s aim was to provide her children with exposure to the best of eastern culture’s music. “When we were young, only folk music, classical, neem classical, qawwali etc. would play in our house,” he remembers fondly. “When we would travel to Islamabad in the car, with our parents, or Murree, or Nathia Gali, they would play these songs as soon as the trip would begin. This was the soundtrack to my childhood. These songs are embedded inside of me.”

After school, Ali remembers coming home to find his grandmother watching television as lunch was being served. Ali’s afternoons were filled with the voices of legends like Madam Noor Jehan, as they sang ghazals written by the poets of the Subcontinent — Allama Iqbal, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Bulleh Shah — on television. In the evenings, the children would listen to film songs from Lollywood’s golden era, and the folk songs that would be aired on PTV. “In this way, we were exposed to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan Sahab, Abida Parveen Jee, the finest poets and, also, philosophy.”

At an age when his friends were looking for music to dance to, Ali was obsessively listening to music that ran deep in Eastern Classical tones, which had at that point become a part of him. Finding himself alone amongst his peers in his love for Eastern Classical music, Ali would listen to these songs in solitude. During his teenage years, Ali memorised the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Nasir Kazmi, Mirza Ghalib, and the poets whose verses he heard in the music he so loved. He read translations and interpretations of their poetry, essays and literature on their lives and their verses, in books he found in his father’s library. “While showering, in the car, in the classroom, I would repeatedly sing and imitate the techniques of singers I was listening to, assessing what parts of the throats were being used to create certain sounds.” At the age of 15, in his diary under “Things to do this year,” Ali wrote: learn classical singing.

Ali’s journey of learning eventually kicked off during the snowy winter of his first semester at Harvard University, when he chanced upon a banner calling students to audition for Ghungroo, the university’s South Asian Association variety show. The freshman had never performed on stage before and, when he showed up for the auditions, was met by fellow students representing the rich cultures of their countries. A range of instruments were being played, from the violin to the tabla, there were different dance styles being performed like the Orissi and the Bharatnatyam. Ali was intimidated but auditioned nonetheless, singing Aaj Jaane Ki Zid Na Karo, and was selected by the show’s directors on the spot. They were more than glad to have Ali on board — Pakistani students, they told him, hardly ever showcase the classical arts of their country at these events, so he was a welcome addition.

This comment stuck with Ali and eventually turned into the driving force that cemented his path towards Eastern Classical learning. He thought often, and at some length, about what it is that Pakistan is most known for throughout the world — he felt its culture, so rich and diverse, remained largely overlooked on the global cultural stage.

“Culture transcends religious distinctions. Through classical and folk art, you can win the heart of a stranger, the Other,” says Ali “The strength of societies that have done so successfully is that they’ve carried out a certain kind of diplomacy — they’ve sent their art out into the world and invited the world to recognize their identity through their music, and their dance, and their crafts. If you win people’s hearts like this, it’s a victory that lasts forever.” Ali eventually came to the conclusion that culture, and art, was no less than a Master’s degree, perhaps even more important in Pakistan’s case. Encouraged by some of his professors to explore this avenue further, Ali set his intention upon classical singing.

During his first summer back from college, Ali asked his mother to arrange a meeting with Farida Khanum, who graciously agreed to have mother and son over for tea. In her company, Ali quite boldly declared that he wanted to learn to sing, serenading her with a film song. When met with her praise, he went a step further and admitted that he wanted to sing classical music, like her. So far jovial, offering tea and biscuits and making light conversation, Farida Sahiba became serious now. “Son, music doesn’t come so easily,” she told Ali, “Seat yourself at the feet of an ustad (teacher), forget all concept of time, and give yourself over to your ustad. Only then, if your ustad sees fit, and if it’s written in your destiny, will you be given something in return.”

Ali found his ustad a year after he graduated from Harvard, a year that was spent searching for the right teacher and researching on classical music. “I came upon Ustad Naseeruddin Saami in a Lahori drawing room, singing a raag of the afternoon,” recalls Ali. Ustad Saami was teaching a friend of Ali’s and invited him to join in. Immediately, the teacher picked up on some things in Ali’s techniques that were working for him, and some things that needed to be changed. And so, Ali found his ustad.

When Ali talks about Ustad Saami, the adoration is obvious in his voice: “There’s so much beauty in Saami Sahab’s way of teaching. I think I’ve found a teacher who is exactly right for my personality.” With Ustad Saami, Ali’s learning has gone beyond just the techniques of classical singing: he has been exposed to an education in Arabic and Persian, been given lessons on history and spirituality. Twelve years later, Ali still considers himself a student — from Farida Khanum, he learns ghazal and thumri, and from Ustad Naseeruddin Saami, he learns classical singing and khyal gaiki.

Over these twelve years, his romance with classical music and poetry has only deepened, the two artforms have become inseparable from the man. He talks about his favorite poets as if they were his close friends, companions to him in his sorrows and his victories. For Ali, music — and poetry — are artforms that can conquer anyone: “Farida Khanum once said to me that if you affect someone’s heart through music then all distances — all suspicions, sense of alienation, material dualities — are wiped away for a bit.” Music is a “miracle” to Ali and when you add poetry to it, the sum of the parts is, quite simply, “magic”.

It’s a weapon, the nexus of poetry and music, Ali explains — a weapon that can be used to wage a personal war, a war of love. It allows the artist to express themselves, more than fully: the music is giving expression to the artist’s meaning, and so are the words. The visuals and metaphors of the poetry package these meanings in multiple ways of being perceived, allowing audiences to receive them according to their own subjectivities. This does not compromise the meaning of what the artist is saying, explains Ali: “You are not surrendering your meaning. You are inviting the other person towards your own experiences; you are luring them through your art. You want to bring them to that meeting space where the differences between you and them are wiped away. So that when they return to their lives, they do not feel like they have met an Other. They feel like they have met themselves.”

For Ali, this interaction is not one-way — his art is a way of connecting to the world around him, a constant reminder that he is joined with people by the commonality of the human experience. “Ashraful makhluqat” explains Ali, is not perfection, it is a state of intermediacy, the human condition of always being separated from an ideal existence. One is not entirely empty, but one is never complete either and, within the empty spaces exists the fuel to one’s art: the firaq (disconnect), the desire for what is absent, the dard (affliction). For Ali, these inhabitants of his empty spaces are a blessing and a gift, to be acknowledged and cherished. They are meant to be presented to the world because they have a home in all of us.

“If you express your pain through art, you will emerge from your solitude into a space where you will be united with others,” he says. “When you express what’s in your soul through music, through poetry, other people will recognise their own pain in it. In the process, what is empty within me meets what’s empty within you, they are connected somehow.” The miracle of music and poetry – connecting societies, wiping away cultural, racial and ethnic differences – works its magic between Ali and his audiences. So that when they return to their lives, they do not feel like they have encountered an Other — through the guise of Ali, they return feeling like they have met themselves.