Fareed Ayaz & Abu Muhammad

by Ayesha binte Rashid

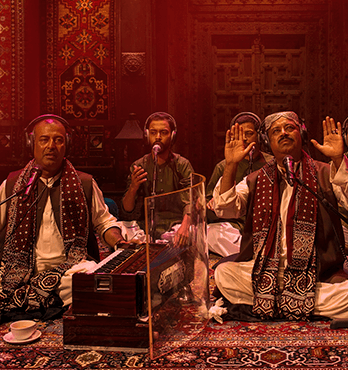

In the artist’s lounge at Coke Studio, Fareed Ayaz and Abu Muhammad take a moment to rehearse as a crowd slowly gathers around them. Abu Muhammad is playing a harmonium, Fareed Ayaz is seated on a sofa - their sons are seated around them on the ground. Their voices are at once a beat and a melody, tempo rising and falling like a wave. They are singing in syllables, their words sometimes long and drawn out, sometimes too quick to understand – this is a tarana written by Hazrat Amir Khusrow. Slowly, the room fills up with spectators while others stop to peer in through the doorway, forgetting themselves for a moment.

When Fareed Ayaz begins to talk about qawwali, it becomes apparent that he carries a library on the subject inside his head, dipping into philosophy and history as he waxes poetic about the artform. His conversation is as fluent and engaging as his performances; he enjoys telling stories and draws us in with his animated mannerisms and the descriptiveness of his words.

Fareed Ayaz is uncompromising in his craft – on set, before the recording, his sons and nephews repeatedly go through each section of the piece they are about to perform. If any one of the six fall out of tempo or tune by the slightest degree, too slight to even be noticed by an unfamiliar ear, Fareed Ayaz picks up on it immediately, and the culprit is guided with a quick correction. This routine is repeated until he is satisfied, after which he turns his attention to the rest of the set, listening through headphones to the other instruments. A slight adjustment to the tuning of the benjo, a quick discussion on the beat of the dholak and only then Fareed Ayaz is ready to record.

To Fareed Ayaz’s melody, Abu Muhammad provides the harmony – he leads rehearsals alongside his brother on the harmonium. When the answer to a question takes a turn that is too philosophical or too metaphorical, Abu Muhammad enters the conversation and steers it towards its conclusion. His presence is subdued but, when he speaks, one is prompted to lean in and listen carefully and when his voice calls out from the stage, its timbre permeates, catching us off guard, demanding a pause to listen.

Fareed Ayaz and Abu Muhammad are masters at what they do; they are sons of Ustad Munshi Raziuddin and heralds of the Qawaal-Bachcha gharana of Delhi. They trace their scholarly lineage to Hazrat Amir Khusrow, a pioneer in qawwali and Eastern Classical music, and are descendants of Mian Samad bin Ibrahim, Khusrow’s first and oldest disciple. For the two brothers, their art is more than a form of entertainment or a profession – it is their inheritance and they see it as their obligation to preserve this inheritance with a sacred form of reverence, as is the custom in Sufi tradition.

In recent years, as the ensemble came to the limelight through mainstream platforms, the brothers have gained popularity amongst a younger generation of qawwali enthusiasts and now find themselves at the receiving end of questions about their genre and the poetry they read; which they entertain happily. The duo considers it their duty to bring pure music to the world and, to them, qawwali is an emblem of the purity of music, Fareed Ayaz explains. It is an all-encompassing genre of music, sinf-e-mosiki. In qawwali, we find thumri, dadra, ghazal and the entire wealth of musical tradition that the world of Eastern Classical music has preserved through history. For the duo, the purity of qawwali runs much deeper than its aesthetic and the two brothers are unwavering in preserving the sanctity of their artform.

“Qawwali is a means of passing on knowledge,” explains Fareed Ayaz. It is a tradition that is meant to pass down the words of scholars and philosophers on the spirit, and that which is Divine. This knowledge, packaged in the form of qawwali, is meant to provide the listener with peace and comfort.

“Your soul and your ears seek what is pleasant. What are you giving to your soul? It’s necessary for the soul to listen to and understand what is pure, and to act on it. The soul will find nourishment in this,” Fareed Ayaz explains, and Abu Muhammad sums up, “Look for peace in qawwali, look for pure knowledge in qawwali.” “Qawwali mein aapko taskeen milti hai, milti hai, milti hai!” concludes Fareed Ayaz with a flourish, “In qawwali you will find peace, you will, you will, you will!”

Understand the gift of qawwali and it will become delightful to your ears, whether the words are in Arabic, Farsi or Barj, Fareed Ayaz explains – dipping into his wordplay, he declares it can move you to euphoric abandon. This is something Fareed Ayaz and Abu Muhammad live by and, having experienced it countless times, they continue to share this gift as a way to feed the soul and ultimately provide peace to one’s being.