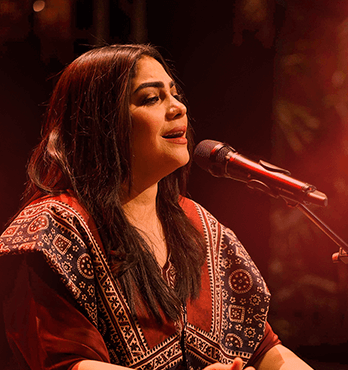

Sanam Marvi

by Ayesha binte Rashid

For Sanam Marvi, the relationship with her craft transcends into the realm of the spiritual. She talks about raags as if they were alive, describing how they speak through her, weaving in and out of the music at their own will. “This is the raag’s choice, I have no choice in this,” she says. “Raags are pure,” she explains, “[They] transport a person into another world.” When Sanam sings, she feels her surroundings change, colors shifting as raags change. When she sings Raag Bhairvi, the color yellow is accentuated in lights around her, white highlights appear when she sings Bhopali, and other colors become prominent with other raags. For Sanam, her experience with raags becomes a dance of color.

In a relationship that had begun when she was just a child, Sufi music has kept Sanam anchored and provided a guiding light during years of grief and loss. She has seen both her father and her first husband murdered, and spent a year separated from her first daughter due to familial conflict. But for Sanam, these ordeals have, however, been peppered with a Divine Providence that today cements Sanam’s belief in the miracles of her God. When she was a child, Sanam’s widowed mother married her step-father Fakir Ghulam Rasool, a man who adopted Sanam as his own daughter. “I find him to be less a human and more of an angel,” Sanam breaks into a smile when asked about him.

Fakir Ghulam was a Sufi singer and an ustad of music — he would travel through Sindh, singing the poetry of Sufi saints in shrines and gatherings. When Sanam was 7 years old, he decided to pass his craft on to his daughter, and so, in the small village of Khairpur Nathan Shah, Sanam’s journey towards Sufi music began. She would wake up before sunrise every day, at Fajr, and her riyaaz (singing practice) would begin with the first light of day, going on for up to four hours. Fakir Ghulam began by teaching her the poetry of the Sufi saints, instilling within her with a deep understanding of the verses she was to sing. Her musical learning included theory, discussions on the effects of raags, the influences they have, and the sacredness of their knowledge.

Fakir Ghulam Rasool recognized Sanam’s path in life early on, saying to her once, “Your voice is Sufi, you’re meant for this genre alone. Now I leave it up to you to decide what you’d like to do.” It didn’t take long for Sanam to decide. On a warm summer evening, Nathan Shah’s children were invited to a local landlord’s home to watch PTV on what was the first television in the village. Sanam still remembers sitting on the courtyard floor, watching Abida Parveen singing Tere Ishq Nachaya on that television, the deep timbre of her voice calling out the frenzy of Baba Bulleh Shah’s poetry. Sanam went home and declared to her father that she wanted to sing like Abida Ji. “Can you imagine, what gall, that I was saying I want to sing like Abida Bibi,” she laughs now at the childhood memory, speaking of Abida Ji reverently, “If I think about it now, such foolishness to say that, she is my ustad, my murshid.

With her heart set on this path, Sanam dedicated herself to her craft and her repertoire expanded under her father’s watchful guidance. Her days became populated with more teachers as she began rigorously training. When she was nine years old, Sanam’s father placed her under the tutelage of Ustad Fateh Ali Khan of the Gwalior gharana, with whom she deepened her learning of Eastern Classical music. She also covered neem classical music, extensively studying thumri from Ustad Majeed Khan in Hyderabad, building an expansive musical range during the course of her learning.

Sanam always returned to her roots in Sufi music, performing with her father in the shrines of Sindh. “I commenced my relationship with raags from the shrines of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Sachal Sarmast and Qalandar Pak,” she recalls. In her childhood, Sanam spent days and nights at these shrines, singing the raags and poetry that she was being taught by her father and teachers. While she was performing at Umarkot’s Marvi Qilla, Sanam’s voice so affected an audience member that he stood up and claimed, “From today onwards, you are our Marvi,” referring to Marvi from the famed folk tale of Umar and Marvi. From then on, Sanam became Sanam Marvi.

Through the struggles she was to face later in life, Sanam’s relationship with Sufi music guided her. “I have powered through many things in life because of Sufism. Whenever I’ve felt that I’m losing life’s battles, I’ve listened to Sufi kalaam (poetry), thought about them, understood them, and learnt from them.” Through success, too, Sufi music remained Sanam’s strength and beacon — after her second marriage, she came to Lahore and was discovered by Mian Yousuf Salahuddin. The deep resonance of her voice caught hearts across the country and eventually gained her international audiences. Whether she sings to a sold-out theatre in New York, or at a shrine in Punjab, Sanam sings in the colors of Sufi music. “My whole life is Sufi,” she says simply.

When she’s not singing, Sanam’s presence is subdued — she speaks softly and picks her words carefully, lapses into quiet thoughtfulness when left on her own. She’s modest about her talent and the learning it stems from, shyly confessing to the house band that she’s nervous during a rehearsal. It doesn’t take much to bring out the magnetic timbre in her voice, however, the reverberations that carry with them an energy that is Sanam’s and Sanam’s only. At a moment’s notice, she launches into raags, and the Sanam that gripped the audience at Marvi Qilla shows herself.

When she talks about Sufism, about what it’s taught her, Sanam’s eyes light up, her tone becomes more intent. “Sufism tells you to ask from your Rabb (God). Everything I have is from Him,” she explains. The light of Sufism has led her to see life as a miracle, “At every step I see a moajiza (miracle). Me sitting here is a miracle, me talking to you is a miracle. If you look at my life: my whole life, and to survive what I have survived, is also a miracle.”