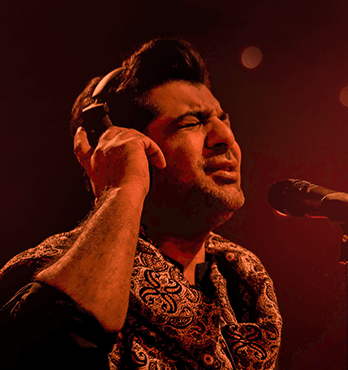

Shuja Haider

by Ayesha binte Rashid

Shuja Haider is always singing. He hums to himself while he walks around, while he sits and waits and while he writes down lyrics. When he talks about a song he likes, he inevitably lapses into its singing parts. Music seems to come to him instinctively and this isn’t a surprise considering he has been surrounded by it since he came into this world.

Shuja’s grandfather, Master Sadiq Ali, was a renowned pianist and his father, Sajid Ali, was also a musician. Shuja’s childhood memories revolve around music – he remembers paying attention to the background scores in the Tom and Jerry cartoons he watched with his brothers and listening to Bee Gees and The Carpenters on cassettes that were bought by his uncle from his travels. “When I heard Karen Carpenter, I was blown away,” he trails off mid-sentence and starts singing the lyrics to This Masquerade. “Lahore’s rainfall and that song playing on a tape. I can never forget those memories. There was a space next to our house, a totally rural environment in the inner city, where people would tie their horses. In an inner-city neighborhood, we would be listening to Queen,” he says and again, starts singing, this time Queen’s Who Wants to Live Forever?

Shuja and his brothers grew up surrounded by some of the finest of that era’s music industry: artists like Khursheed Anwar and “Nayyara Aunty”, were those who frequented the iconic Evernew Studio, where some of cinema’s most iconic tunes were produced. Exposure to composers such as Arshad Mehmood and the duo Bakshi-Wazeer was a regular part of their lives. For Shuja, it was a privilege to see these masters at work. “I’m very lucky that I saw them making songs. It’s by watching them that I learnt a little about how a song is made, how it’s weight should be distributed, and what tempo it should be in.”

Shuja’s own career started in Lahore’s famed Heera Mandi.

Playing in Heera Mandi was not a pleasant experience; performers were often mocked and shamed by the audience who considered them to be inferior. Shuja recalls how people would freely shout lewd comments or slurs on caste and status towards the entertainers. Amidst swears and profanities, guns would be shown and audience members would gleefully fire them into the air. Shuja shares a memory of one particular show in which attendees were showering performers with thousand-rupee notes, as is common at such gatherings. Shuja, seated on the stage floor playing his guitar, stared at the shower of notes. “They say in Punjabi na, ‘ Chaunkri maar ke bethen (sitting cross-legged)’,” he lapses into Punjabi as he remembers the incident. His legs were eventually covered with notes while, at home, Shuja’s family didn’t have enough money to buy food.

The struggling musicians around Shuja started collecting the money, stuffing handfuls of notes into their bags with haste. Silently playing his instrument, fourteen year old Shuja had tears in his eyes. “I told myself, ‘Yaar, Shuja if you pick up this money today, then you will keep picking it up. This will become your life.” He collected his Rs. 300 payment for the show, stopped at Arif Hotel on his way, bought rotis for his family and went home.

Some years prior to this incident, his family had moved to Karachi and thrived in the city, where they had maintained a comfortable life. An unfavorable situation caused them to move back to Lahore, which they discovered was a changed city. Their acquaintances and professional contacts had moved on in life, and the music industry had changed. The family fell on hard times, out of place in a city they had once called home.

Music wasn't a career Shuja had ever considered seriously. “Songwriter is a tall order, I didn’t even want to ‘lalalalala’ at that time,” he says. When his family fell on hard times, Shuja decided to step up and help pay the bills. Having grown up around music, he had naturally grown to possess the necessary skills – music was all he knew, so music was what he did. He didn’t know then that he would be Shuja Haider one day; the music composer who is returning for his sixth performance on Coke Studio. But he decided to try anyway.

“That space, that situation, it gave me an opportunity, a field to play. I played my innings. And I was rewarded,” he ponders in the jargon of his favorite sport.

The innings were not easy, or comfortable. Eventually Shuja and his father moved to Karachi along with his younger brother. What followed were two months of sleeping on mattresses placed on a factory floor which was surrounded by machinery.

“I would travel alone on a bus. I must have toured all of Karachi telling people I make music,” he remembers with a laugh. There is no bitterness in him when he recalls these memories. “You know that metaphor of a wheel, when it’s thrown from the top of a mountain? It stumbles and it meets bumps on the way to its destination at the bottom. There’s such a force acting on it; it doesn’t stop. I was that wheel. I stumbled, I met bumps, but I wasn’t stopping.”

And it was this bumpy road that led to opportunities that gave rise to Shuja Haider. Haroon of Haroon Ki Awaaz introduced him to digital music production at a time when computer technology had newly infiltrated into this part of the world. Soon after, Ghazanfar Ali launched Indus TV and Shuja was on the team of music producers whose talent was incubated behind the scenes on the channel. There he met Bilal Maqsood and Faisal Kapadia and worked with them on Mera Bichra Yaar and Mere Sohniye– two songs that any Strings fan can launch into at a moment’s notice. The more he worked, the more work he got.

Shuja’s story isn’t a sad story and he doesn’t want you to see it as one. Talking to him, you’d think he considers it a happy story and he keeps coming back to the same point: he is lucky to have experienced all that he did. Because for Shuja, experience has been the greatest teacher, teaching him everything he knows today, giving him a chance to be hopeful and prove his resilience. Looking back on all of it, Shuja only has gratitude for his journey.

When he was a teenager, Shuja came home one day to find that his mother had sent his younger brothers to Data Darbar to get langar – free food that is distributed at shrines – because there was nothing to eat at home. Shuja was furious. Lining up for langar meant having to joust people as everyone shoved and pushed to get to the front. Those managing the line would sometimes use sticks, hitting people to keep order and Shuja did not want his brothers to be put in that position. Shuja rushed to the darbar to find them but, once he was there, the smell of the langar tempted him into getting in line himself, since he hadn’t eaten himself. That day, he had a passing thought. “Baba Jee, I don’t want to be stuck here. Help me.” He doesn’t know how it happened, why it happened, when it happened. But it happened.